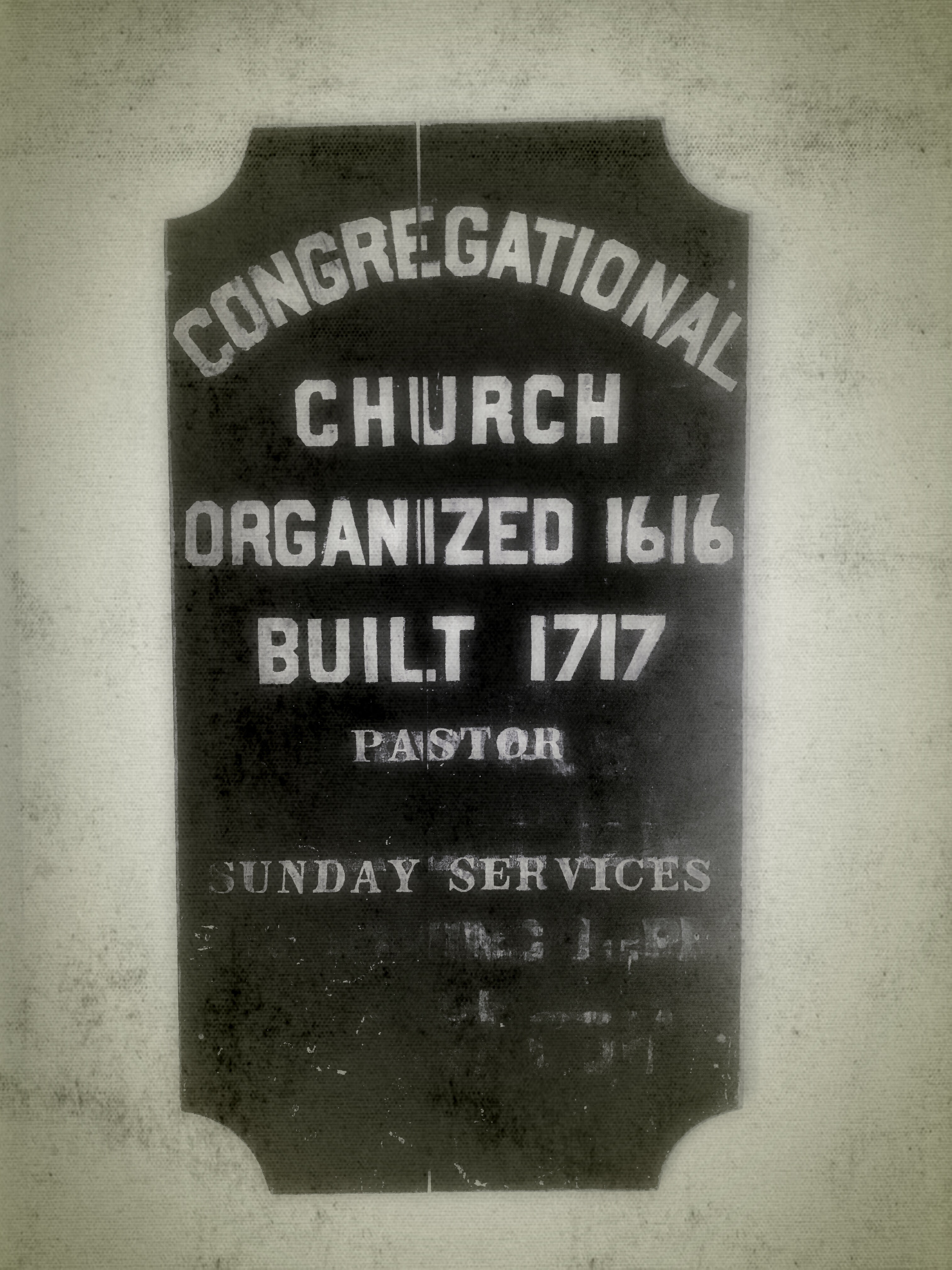

West Parish of Barnstable helped to define the Congregational tradition, as it is the oldest continuous congregation of any denomination in New England – dating back to 1616.

The very same motivation that drove the founders of this congregation from the London borough of Southwark, continues here today with our independent Congregational focus of loving inclusion which blesses this community ever since those worshipers were granted land in Mattakeese (now Barnstable) in 1639. History happens here! God gathers you here!

(For a more thorough history of the physical 1717 Meetinghouse, including famous visitors and historical debates, please visit our independent and non-sectarian sister site – www.1717meetinghouse.org.)

What is a Congregational Church? Wikipedia defines it succinctly: “Congregational churches are Protestant churches in the Reformed tradition practicing Congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its own affairs.” In the colonial era in New England, what is now referred to as the Congregational Church was the standing church of the Colony.

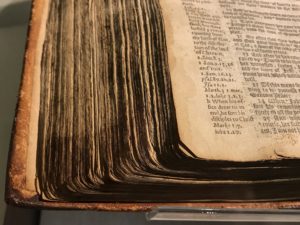

What differentiates Congregational theology, from other Christian beliefs? In the English tradition, one can point to Henry VIII and his founding of the Church of England. In 1531 King Henry VIII broke away from the Roman Catholic Church to become the Supreme Head of the Church of England. Within fifty years, theologians such as Robert Browne embraced the teachings of John Wycliffe of 200 years prior – who believed that each distinct congregation fully constitutes the visible Body of the church. The two founding tenets of Congregationalism are sola scriptura (the Bible is the sole rule of faith and practice), and the priesthood of believers – that through Christ, God is equally accessible to all the faithful, that every Christian has equal potential to minister for God.

This congregation was founded on those very principles in 1616.

Pastor Henry Jacob – an ordained priest in the Church of England, broke with the established church, and founded the first independent church in London which survives in worship here today – over 400 years later. Calling themselves “Congregationalists”, the small group of followers worshipped in secret, for if discovered, they would be considered traitors to the King and the Church of England.

Pastor Henry Jacob – an ordained priest in the Church of England, broke with the established church, and founded the first independent church in London which survives in worship here today – over 400 years later. Calling themselves “Congregationalists”, the small group of followers worshipped in secret, for if discovered, they would be considered traitors to the King and the Church of England.

In 1623, The Reverend John Lothropp – also a priest in the Church of England – succeeded Henry Jacob who had been imprisoned as a traitor to the Church of England. His followers continued to worship in secret, until April 22, 1632, when the King’s officers discovered the covert worship and imprisoned 43 members, including Rev. Lothropp. They remained in prison for two years, and finally released to be exiled in the new world since they would not take an oath of loyalty to the Church of England.

On September 18, 1634, the widowed Reverend Lothropp, his surviving children and 30 of his followers disembarked from the ship Griffin after a month and a half voyage from London. Settling in Scituate, MA, Rev. Lothropp continued to lead his congregation, until a land grant by Plymouth Colony Governor Prence was awarded the group. This land on the Cape offered better prospects for agriculture and cattle grazing. One of those original followers was the deacon William Crocker; it was from his descendant John Crocker that land was acquired on which the present 1717 Meetinghouse has crowned for over 300 years.

Rev. Lothropp and 22 members of his congregation left their Scituate homes and began to make their journey to Mattakeese on June 26, 1639. One group drove livestock over the land for 60 miles, and another group followed by water crossing nearly 40 miles of Cape Cod Bay. By October 11, 1639, Lothropp and his followers joined previous settlers and friendly Wampanoag Native Americans to found the Town of Barnstable, named for the English town of Barnstaple, which shared similar topography.

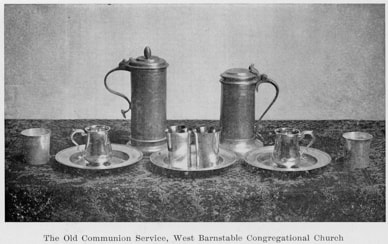

Now, alone in Mattakeese, using the same pewter vessels the congregation had brought with them on the Griffin, the first Sacrament of Communion was celebrated at Sacrament Rock, just off Old Kings Highway (Rt. 6A). Church services would eventually be held in Rev. Lothropp’s home, which now forms the core of the Sturgis (Barnstable Public) Library. In 1646 a small Meetinghouse was built at Lothropp Hill (which was later replaced in 1681 with a larger Meetinghouse at nearby Coggins’ Pond). Rev. John Lothropp passed in 1653, after leading his congregation in Barnstable for fourteen years, and after a life’s journey of great conviction and personal sacrifice toward religious freedom.

By 1717, Barnstable had grown so large that the Town Meeting had decided to divide the town into two precincts – East and West Parishes – West Parish serving the villages of Cotuit, Marstons Mills, Osterville and of course West Barnstable. Construction of the West Parish Meetinghouse took two years; the first service of worship was on Thanksgiving Day, 1719. After just four years the Meetinghouse was deemed too small; it was divided in half: the ends were pulled apart by 18 feet and widened. A bell tower – one of the first in New England – was erected, and the gilded cock was ordered from England to serve as a weathervane. That Rooster still crowns the tower today.

25 years before the construction of the 1717 Meetinghouse, the Massachusetts Charter changed the former Plymouth Colony’s base from theocratic to political and secular. In Massachusetts however, the Congregational Church remained the established church. Taxes were still levied by the towns for the support of local churches, whose buildings served dual purpose as houses of worship and a place to hold town meetings. Further, the first school classes in Barnstable were taught by the minister in the North-East loft area of the 1717 Meetinghouse. This blended relationship of church and state continued until 1834, when the church was “disestablished in Massachusetts.”

Congregationalism took firm root early-on in New England. Harvard was founded in 1636 as a Puritan/Congregationalist institution to ensure the colony had a supply of educated ministers. In 1701, 65 years later, Yale was also established by clergy to educate Congregational ministers. Congregational churches and ministers influenced the First and Second Great Awakenings. The Congregational tradition shaped both mainline and evangelical Protestantism in the United States. And, more shattering in New England, it influenced American Unitarianism. New England Unitarians evolved from the Pilgrim’s Congregational theology, and became a new force in the then contemporary theology.

The Unitarian Henry Ware became the head of the Harvard Divinity School in 1805; this signaled the changing theological tide from traditional or orthodox Calvinist teachings to more liberal Unitarian ideas. Being independently governed, West Parish remained orthodox, and East Parish embraced the more liberal Unitarian beliefs. The original Congregational Charter was continued with West Parish, and the London-era sacramental vessels would be shared between the two parishes. East Parish became known as a Unitarian church. Other towns in Massachusetts did not have such a harmonious split between orthodox and liberal members; often is the case the Unitarian Church would legally occupy a town’s “First Parish Church”, and a block away, a Congregational church would be built in the early-mid 1800s to become the new home to the ousted orthodox Congregational minority (or sometimes majority).

Following the 1834 act in Massachusetts separating church and state, a separate Town House was built in 1837 for civic meetings; that building still stands at the corner of Oak and Old Stage Road in Centerville, and currently hosts the Veritas Academy. Given the lack of financial support from the town, the 1717 Meetinghouse fell into disrepair. Likewise, given the formal split between orthodox and liberal theology, the West Parish members were faced with the prospect of demolishing the old Meetinghouse (as many communities did) and building a new purpose-built church, or remodeling the existing structure.

In 1852, West Parish members opted to remodel the 1717 Meetinghouse into a neoclassical design. Gone was the bell tower, but the 1806 Revere bell was moved into a new traditional steeple. Taller windows were installed, a ceiling was raised below the massive Meetinghouse beams, and the main entrance was moved to face the street – under the steeple and Greek-style pediment. Luckily, underneath it all, remained untouched the original structure – complete with the original frame, beams, floors, walls and roof.

Elizabeth Crocker Jenkins

Today, history still happens at West Parish of Barnstable; the history of the congregation is its parishioners! Sacred life passages are celebrated here (whether one is a member or not); the West Parish congregation continues to serve the community. Those same Congregational tenets for which our Congregationalist forbearers fought, and were even imprisoned and exiled – 400 years ago – are still found here today. The Congregational traditions on which this faith was founded – your direct and personal relationship with Christ, your direct governance of the congregation, and your personal community of open and inclusive love and support, still happens here!

Today, history still happens at West Parish of Barnstable; the history of the congregation is its parishioners! Sacred life passages are celebrated here (whether one is a member or not); the West Parish congregation continues to serve the community. Those same Congregational tenets for which our Congregationalist forbearers fought, and were even imprisoned and exiled – 400 years ago – are still found here today. The Congregational traditions on which this faith was founded – your direct and personal relationship with Christ, your direct governance of the congregation, and your personal community of open and inclusive love and support, still happens here!